By Stephi Cham | March 2023

Houston Methodist Hospital (HMH) is proud to offer art therapy as a complimentary service to our patients through the Center for Performing Arts Medicine (CPAM). Addy Purdy is CPAM’s Art Therapist.

Having loved art throughout her life, Addy uses her training and passion to serve patients in multiple areas across HMH.

According to the American Art Therapy Association, art therapy is an “active and integrative mental health and human services profession that enriches the lives of individuals, families and communities through active art making, creative process, applied psychological theory, and human experience within a psychotherapeutic relationship.”

Licensed art therapists use art therapy to “improve cognitive and sensorimotor functions, foster self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience, promote insight, enhance social skills, reduce and resolve conflicts and distress, and advance societal and ecological change.”

Pathway to Art Therapy

Becoming an art therapist requires rigorous education and training—and at least several years.

Addy first realized the impact of art in college. Her coursework and supervised art-making experiences at Cook Children’s Hospital led her to pursue a Master of Art Therapy from The George Washington University. A master’s degree is required to practice art therapy; educational standards require coursework in the creative process, psychology development, group therapy, art therapy assessment, psychodiagnostics, research methods, multicultural competency development and cultural humility. Students must also complete at least 100 supervised practicum and 600 hours of supervised art therapy clinical internship.

Addy’s journey to credentialing was disrupted multiple times by COVID-19. Internship sites shuttered in-person services, and many no longer accepted interns. Back in Houston, her hometown, Addy struggled to find a site compatible with the school’s affiliation agreement.

Then another art therapist connected her to Jennifer Townsend, manager of creative arts therapies at the Houston Methodist Center of Performing Arts Medicine. CPAM did not yet have an art therapist, but Kate Marder, art therapist in the outpatient behavioral health center, agreed to supervise Addy.

Balancing two internships with CPAM and Cypress-Creek Psychiatric Hospital with Art Therapy Houston, Addy worked with multiple patient populations. “I [saw] how beneficial art therapy in the medical setting really was across the board,” she says.

Amidst the uncertainty and tumult of COVID, Addy worked primarily in inpatient acute care but saw patients throughout HMH. She formed connections with both patients and staff, co-treating with other medical personnel including music therapists, social workers and occupational therapists. “Although I was the only one in the field of art therapy in CPAM, I was welcomed into and became a part of a team that was so supportive and knowledgeable that I felt right at home,” Addy says. “I knew I wanted to work here.”

After receiving her Registered Art Therapist-Provisional credential and LPC-Associate certificate, Addy began working part-time as an Art Therapist at HMH; this month, she began working full-time at HMH. “I still work mostly with heart transplant patients through their journeys, but I [also] get many different referrals throughout the hospital,” she says. After she completes 1,000 hours of post-graduate direct art therapy practice and 100 hours of supervision, she will take the Art Therapy Credentials Board Examination to become board certified, ATR-BC. And, after working 3,000 hours under the supervision of a Licensed Professional Counselor-Supervisor, she will become an LPC herself (without the Associate provision).

Art Therapy at Houston Methodist

“There is no judgment in art therapy,” Addy says. However, people with varying levels of artistic experience and technique may feel self-conscious or self-critical. Building a therapeutic relationship rooted in trust and goals can bring about creative freedom and direction.

Addy says, “It is all about the process, not the product.”

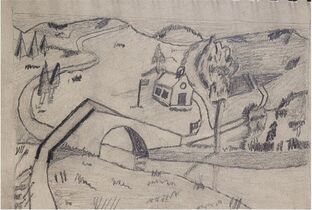

Together, Addy and her patients explore thoughts, feelings, behaviors, relationships and emotions. One common directive she uses is a mindscape, or an emotional landscape (Essential Art Therapy Exercises, Guzman).

“This is where I ask a patient to use whatever materials they would like to create in their mind as a landscape, inviting them to think about what type of scene it might be: a seascape, mountain range, river, city, etc.” Building on details perceived by the five senses, the patient-guided and therapist-facilitated intervention “creates a safe and comfortable place” for external expression of internal processes “in a symbolic and personally meaningful way that can be processed with the therapist.”

She sometimes uses a directive based off the bridge-drawing assessment (Hays & Lyons, 1981), where she invites patients being evaluated for or going through the heart transplant process to create an image of a bridge and prompts them with questions such as what the bridge is made of or where it leads to.

“I’ll ask the patient to indicate where they are in relation to the bridge, and we’ll discuss how the aspects within the image and what the patient is saying about it relate to their transplant journey. Patients before transplant and during evaluation typically place themselves before the bridge, approaching it. Patients who have been accepted and are listed might put themselves on the bridge towards the beginning.”

In the medical setting, patients’ treatment goals and medical status can change significantly from day to day and even moment to moment.

“People can decline and improve rapidly. This is when treatment changes. For example, if I’m working with a patient who is actively engaging in art making within treatment prior to transplant and they begin to decline or have complications, we might do some more passive engagement with art viewing and discussion,” Addy says.

Her work, drawing on her artistic and clinical judgment, training, and intuition, is highly adaptive to meet individuals’ needs. She has used mandala-based coloring sheets, taught artistic coping skills like crochet, and provided art psychoeducation to assist in coping with hospitalization.

One technique she teaches is meditative painting, especially for patients with a history of anxiety or anxiety related to hospitalization and treatment. Watercolor paint combined with water—first a large amount of it—saturates the paper to “create a wash of desired colors without an intention.”

“Once the paper is filled with color, one can look into the artwork they’ve created and emphasize different symbols, forms and images within. This is a process called free association, which can give light to unconscious content, thoughts, desires and fears when processed within the safety of the therapeutic relationship. Even if there is no deeper or symbolic meaning found within the content, the process itself has benefits in regulation, cognitive stimulation and creative engagement.”

Other patients may benefit from entirely different approaches. “I’ve worked with several patients who have woken up from a medically induced coma that experienced altered mental status or delirium. In the sessions they recall dreams or hallucinations that were so vivid they would go back and forth between dream and reality, unable to discern between the two,” Addy says.

Patients sometimes find these visions disturbing or traumatizing. Addy facilitates space to “share, express and process these scenes” to achieve insight and resolution.

Others might glean from these visions hope and personal meaning. “I have worked with patients who have died, flatlined and come back to life to share the sights seen within their near-death experiences. Some patients have seen bright lights and auras, lost loved ones, angels and people they have never met before.”

These experiences can be difficult to articulate or communicate. Art is a different way to express them, opening the way for processing.

“From going through and processing these subconscious or unconscious experiences with different individuals, I think each person sort of gets what they need for themselves when they come back on the other side,” Addy says.

The powerful impact of art therapy is backed by these experiences, patient feedback and research studies. Addy is well-versed in not just exploring and implementing art therapy, but also explaining and advocating to patients, clinicians and many others.

“While it might look like an art class is happening from an outside perspective looking in, there is a much deeper and meaningful process that is happening within each session,” Addy says. “Art therapy is an effective form of treatment that promotes overall wellbeing through the integration of the creative process and psychotherapy, which is grounded in the knowledge of human development, psychological theory and counseling techniques.”